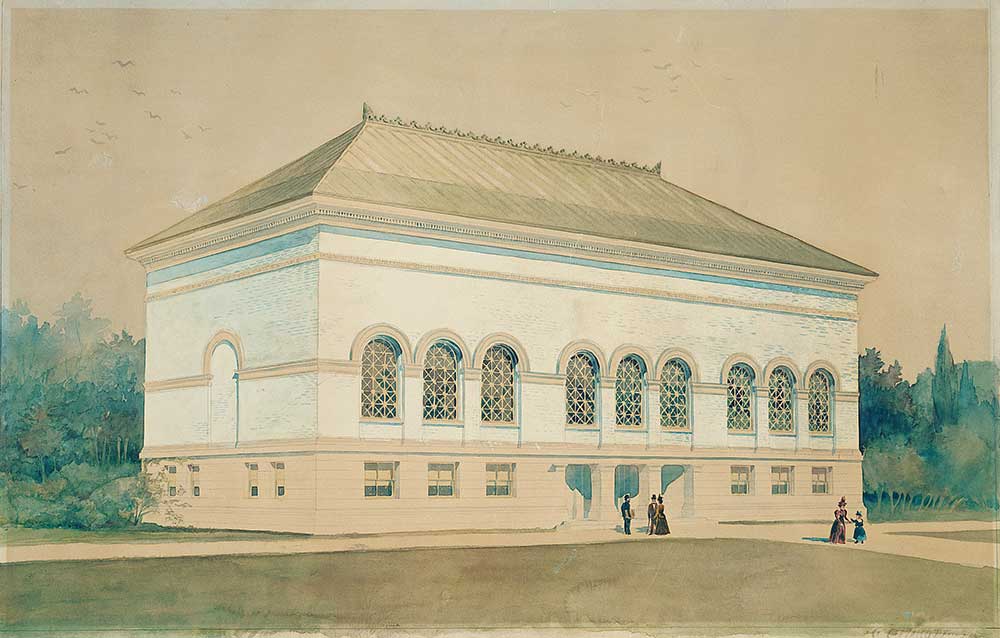

View of the sculpture galleries in the original Museum building.

By the 1890s, Boston, New York, and Philadelphia all had art museums. Worcester philanthropist Stephen Salisbury III believed his hometown deserved one too, and he joined forces with other community leaders to build an art museum for Worcester. They envisioned a museum that would not be a repository of a rich man’s treasures, but an institution created “for the benefit of all.” People of all ages, walks of life, and backgrounds would view masterpieces from around the world and be educated—as never before—about art and the world in which it was created.

Key dates

1898 – The beginning of a great art museum

Salisbury’s vision was realized on March 18, 1897, when ground was broken for the original Worcester Art Museum building. Designed by Worcester architect Stephen C. Earle, it was a handsome structure in the Renaissance style, with light colored Roman brick; tall, arched windows; and polished oak floors. At the time, the cost for the equipped and furnished building was $106,067.25. Although Stephen Salisbury’s gift of land and $100,000 for construction and endowment covered a sizeable portion of the project, it took the generosity of many citizens to make up the difference. The 1898 Annual Report acknowledged gifts to the “Building Fund” ranging from $3,000 to $.25, but donations as low as $.05 had been received.

Even before the doors were opened on May 10, 1898, several additions to the Museum already had been envisioned. In the First Annual Report, the directors wrote of a “great square of buildings that shall form the final museum” and explained that the one under construction would constitute only one side of the court. With foresight and his customary generosity, Salisbury gave an extra tract of land behind the original one to accommodate this future expansion. In addition to increasing the Museum’s land holdings, the gift also allowed the directors to situate the original building forty feet farther back from Salisbury Street than initially planned. Saplings were planted in front of the Museum, and over the years they grew into a lush grove of trees, creating a park-like setting.

Initially, WAM’s collections were modest. Many of the pieces on display were loans. Through purchases and the beneficence of supporters, however, the collections steadily grew. Family portraits by Gilbert Stuart, silver by Paul Revere, and America’s first public collection of Japanese prints soon went on display. The Museum bought works by Impressionists, fresh from their studios. In addition, an art history library was established, and studio art courses and innovative educational programs were developed and offered to the public.

1921 – More space is needed

Urgently needing more room, the Museum did expand, though not quite in the manner that trustees had planned. The first addition was a two-story structure attached to the rear of the original building. When it opened on February 18, 1921, the new wing provided increased space for the library, Education Department, and administrative offices, as well as three much-needed galleries. The cost was $176,000. The new galleries, which are referred to as the Lower Third Floor, allowed for a more logical arrangement of the growing collection, although Director Raymond Wyer acknowledged in the 1921 Annual Report that many would “miss the refreshing spirit which the brilliancy of a Monet gave to an early Italian work.” While commending the recently completed addition, he also hinted that “even now we need more space.”

1933 – A grand new wing

Six years later, in the Thirty-first Annual Report, Vice President Thomas H. Gage reiterated this need for more space. And the following year, in 1928, Director George W. Eggers announced that museum buildings throughout the country were being studied for ideas for a new wing in Worcester. Boston architect William T. Aldrich was finally selected, and in July 1931 work commenced in front of the 1898 building for an addition one-and-a-half times the size of the existing structure.

In the “restrained classic style of the Renaissance,” the 1933 wing was conceived as a series of galleries encircling an interior court. It was not a new concept; indeed, its closest equivalent was the Fogg Museum in nearby Cambridge. But unlike the Fogg, the Worcester building was designed to permit the visitor a complete, uninterrupted circuit of galleries on both the first and second levels. “(The) journey through the galleries will be retrospective and historical,” wrote Director Francis Henry Taylor. “(One) will be able to arrive at certain philosophical conclusions which only travel and wide historical reading man otherwise provide.”

Aside from general growing pains and a philosophical commitment to chronological arrangement of the collection, there was a very specific motivation behind the 1933 addition. In 1927, the Museum had acquired a 12th-century chapter house from the Benedictine Priory of St. John at Le Bas Nueil, near Poiters, France. The new wing was designed around this small medieval building, the first purchased by an American museum.*

At one point, the Romanesque hall had belonged to a Romanian banker, who planned to incorporate it into his chateau. He died, however, before the chateau was done, and the chapter house was bought by a New York sculptor and art collector, who soon sold it to the Worcester Art Museum. For about five years, two shiploads of crates containing carefully numbered stones were stored in the back of the Museum awaiting reconstruction. The stones were finally reassembled in 1933 and since then, the chapter house has not only anchored the Renaissance Court, it has also been one of the most beloved spaces at WAM.

* It is sometimes assumed that the Renaissance Court was designed and built to display the Worcester Hunt Mosaic, which is a focal point that occupies a large part of the hall’s floor space. However, the mosaic did not enter the permanent collection until 1936, three years after the 1933 addition was completed.

1938 – Adding a fourth floor

The Great New England Hurricane of 1938—one of the deadliest storms in recorded history—cut a swath of devasting destruction through central Massachusetts. The Worcester Art Museum was not spared. The September storm caused serious damage to the roof and superstructure of the original 1898 building. When the trustees learned that it would be cheaper to tear down the damaged section and begin anew, rather than repair it, they seized the opportunity to add an extra floor of gallery space. The new fourth-floor galleries were completed in May 1940. At the same time, two large courts on either side of the corridor connecting the 1898 and 1933 buildings were roofed over to accommodate the Museum School, which had been operating out of the nearby Salisbury House.

1970 – The Higgins Education Wing

For nearly thirty years, the Museum turned its sights away from expansion and towards “redecoration,” a policy that prevailed until 1968, when The Architects Collaborative of Cambridge began work on the Higgins Education Wing.

A permanent home for the Museum School and facilities for the ever-expanding Education Department had long been needed. In 1967, WAM received a generous gift from the Aldus C. Higgins Foundation and members of the Higgins family in memory of the late Aldus C. Higgins, a former president of the Museum. This donation, along with a grant from the Department of Health Education and Welfare, made the $1.5 million education wing possible.

Comprised of offices, studios, classrooms, and exhibition spaces for student and faculty work, the 43,000 square foot building opened on May 27,1970. The concrete, L-shaped structure surrounds a garden courtyard, named the Stoddard Garden Courtyard, and dedicated in 1990 to recognize the generosity of the Stoddard Family and Stoddard Charitable Trust. Continuous walls of floor-to-ceiling windows overlook the picturesque courtyard, which was designed to act as a counterpoint to the Renaissance Court of the 1933 addition.

During the 1970s, the Museum again turned inwards. With money raised through the Renaissance Fund, the first capital fund drive in the Museum’s history, the European and James Corcoran Donnelly Galleries, curatorial and administrative offices, Salisbury Reception Room, and library were extensively remodeled. All the while, though, there was an eye towards expansion, for as early as 1965, a new exhibition space had been included in the list of future needs.

About The Architects Collaborative

Co-founded in December 1945 by German architect and Bauhaus founder, Walter Gropius, The Architects Collaborative (TAC) embraced some of the most cherished and derided aspects of postwar architectural design. Working in collaborative groups, TAC architects strived to align architect with art, economics, and sociology, approaching design as a social process that was responsive to the needs of individual patrons and sites.

1983 – The Frances Hiatt Wing

During the 45 years after the fourth-floor addition to the original 1898 building, the permanent collection grew steadily, traveling exhibitions took on monumental proportions, and the conservation facilities became outmoded. A new 24,000 square foot addition was planned to address all of these needs—with galleries for traveling exhibitions; curatorial offices; study and storage areas for the print, drawing, and photograph collections; a conservation laboratory; and space for art storage. Designed by Worcester architect Irwin A. Regent, the new three-story wing was completed in 1983. It houses the Hiatt Galleries, in memory of Frances L. Hiatt, the late wife of Jacob Hiatt, who was chairman of the board at Rand-Whitney Corporation and had been a trustee of the Museum since 1971. Mrs. Hiatt was widely recognized for her leadership in community and educational programs. In addition to Mr. Hiatt, the 1983 addition was made possible due to the great generosity of hundreds of other individuals, foundations, and corporations.

2015 – Salisbury Access Bridge

During the 45 years after the fourth-floor addition to the original 1898 building, the permanent collection grew steadily, traveling exhibitions took on monumental proportions, and the conservation facilities became outmoded. A new 24,000 square foot addition was planned to address all of these needs—with galleries for traveling exhibitions; curatorial offices; study and storage areas for the print, drawing, and photograph collections; a conservation laboratory; and space for art storage. Designed by Worcester architect Irwin A. Regent, the new three-story wing was completed in 1983. It houses the Hiatt Galleries, in memory of Frances L. Hiatt, the late wife of Jacob Hiatt, who was chairman of the board at Rand-Whitney Corporation and had been a trustee of the Museum since 1971. Mrs. Hiatt was widely recognized for her leadership in community and educational programs. In addition to Mr. Hiatt, the 1983 addition was made possible due to the great generosity of hundreds of other individuals, foundations, and corporations.

On November 14, 2015, WAM unveiled a new accessible walkway to the historic main entrance on the Salisbury Street side of the building, which leads visitors into the Museum’s grand Renaissance Court. Designed by Kulapat Yantrasast of WHY Architects, the “bridge” not only significantly improved access, it also boldly combined contemporary design with the Museum’s 1933 Beaux-Arts exterior.

Without altering the Salisbury Street doors or distracting from the formal entrance, the designs honors WAM’s past, while the bridge itself, in its sleek aesthetic and incorporation of minimal shapes, reflects the tastes of today. The bridge’s metallic siding creates a dynamic visual parallel with the columns above.

At the ribbon cutting for the new access bridge, Matthias Waschek, the Museum’s Jean and Myles McDonough Director said, “All our visitors, including those with mobility issues and families with strollers, can now use the Museum’s front door, entering a place of art via a work of art. We want the WAM experience to start well before entering the gallery spaces. As we honor our past, embrace our presence, and look towards the future, this small but thoughtful and very creative project by WHY Architects is just the beginning of many more holistic upgrades to our campus.”

Partial funding for the Salisbury Street Access Bridge project was provided by the Massachusetts Cultural Facilities Fund, as well as the Stoddard Charitable Trust, George I. Alden Trust, and the Fletcher Foundation. This facility project helped earn the Museum a prestigious “Commonwealth Award for Access” in 2015 from the Mass Cultural Council, the state’s highest arts agency.